How Is Beef Ban Against Nationalism

Rumors acquired the death of Mohammad Akhlaq and the severe beating of his son in 2015. As members of Bisara village spread rumors of the family eating and storing beef, a mob formed and stormed Akhlaq's house. Akhlaq'south girl, Sajida, described the night her father was killed: "They defendant us of keeping cow meat, broke downward our doors and started beating my father and brother. My father was dragged outside the house and browbeaten with bricks. Nosotros came to know later that an announcement had been made from the temple nearly us eating beef," she told reporters.

Bharat's ordinance to protect cows due to their political and commercial worth bans beef consumption, making it illegal to eat beef and warranting a fine or prison sentence. Following heightened Hindu nationalism, the beef ban in Bharat targets people who are suspected of consuming meat due to their proximity to cows, primarily targeting Muslims and Dalits. Sajida explained that her insistence that at that place was "mutton in the fridge," not beef, failed to dispel rumors of her family consuming cow meat, and over a hundred people marched from the temple to her family unit's house on the night of the attack. Akhlaq'due south murder is non an isolated example. The 2015 ordinance banning the slaughter and consumption of beef turned a long-standing upper-caste Hindu taboo into police and sparked a ascent in violence confronting people who practice not—or are rumored to not—comply.

The ban has unleashed violence towards individuals suspected of carrying beefiness.

The police force responded to the murder of Akhlaq and beating of his son by sampling meat from Akhlaq's fridge for forensic testing to determine if it was indeed beef. This might seem similar a strange response; what does it affair, now that a man is dead? Beef-testing kits are, still, one of the many new technologies that Republic of india'south Hindu nationalist regime has proposed in an effort to enforce the beefiness ban, monitor cows, and stalk vigilante violence directed mainly against Muslims and Dalits.

Simply will these technologies actually reduce vigilante violence? And is safe actually even the goal? We argue that increased surveillance of certain bodies—both human and bovine—actually creates further vulnerability beyond the human and not-human spectrum. The authors accept analyzed trends and commonalities found in over 700 media articles about the beef ban; nosotros accept plant that the government'southward use of engineering science, such as beef antibody detection kits, to monitor and ostensibly protect cows has in fact legitimated existing biases and worked manus-in-hand with the rise of bodily violence against marginal groups.

Cow protectionism

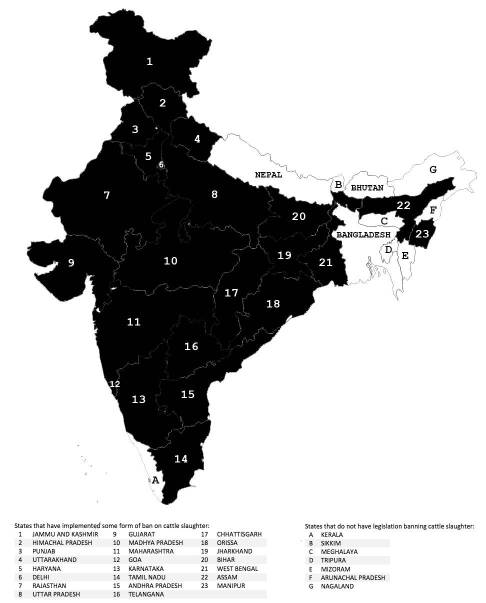

In India, an upper-degree Hindu taboo confronting beef has translated into a policy banning cow slaughter in numerous states. Historically, a beefiness taboo amidst upper-caste Hindus arose in around the first century C.Eastward. The cow continues to be viewed as sacred within Hinduism and beef consumption is taboo for caste Hindus. Narendra Modi's election as Prime Minister in 2014 and his involvement in the Hindutva (Hindu nationalist) beliefs of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) supported a rise in Hindu nationalism in India. The 2015 ordinance passed during Narendra Modi's first term as Prime number Minister draws on the Indian constitution's recommendation to protect cows based on their political value and commercial worth by making cow slaughter and consumption illegal in various states.

The law specifically targets Muslim and Dalit groups who, forming a asymmetric share of leatherworkers and butchers, are associated with cow ownership and consumption. The ban has unleashed violence towards individuals suspected of carrying beef. Between May 2015 and December 2018, 100 people were injured of whom fifty percent were Muslim, ten per centum Dalit, nine percent caste Hindus and three percent various tribal groups. Forty-four Indians had been killed equally of Dec 2018, of whom thirty-vi were Muslims. A significant proportion of these and other hate crimes were initiated by rumors spread through social media platforms. Technologies developed to monitor moo-cow slaughter, cow meat sales, and beef consumption also target Muslim and Dalit people. Technological surveillance of cows and cow bodies does little to protect Dalit and Muslim people from rumors and hate crimes, and in fact heightens the surveillance and policing of people whose livelihoods are oftentimes tied to the cows.

In our contempo qualitative written report, we analyzed over 700 news articles written about the beef ban between early on 2015 and mid-2016. Nosotros found a consistent apply of 'science' to justify the ban. These technologies placed groups deemed 'suspicious,' predominantly Muslim and Dalit individuals, under heightened surveillance, pressuring them to discipline themselves to avoid violence, and contributing to their sense of fear and exclusion from the nation. Self-discipline has resulted in some meat store owners trying to obtain ELISA kits to use themselves in case they are e'er defendant of selling or consuming beef, not wanting to take a chance having their meat confiscated, and to deter vigilante violence. Mohammad Akhlaq's murder was traced to potential beef consumption, where the "solution" proposed was for law to bear beef detection kits to test meat samples within a quick timeframe and to (purportedly) stem violence. Focusing on cow meat and the cow'due south body as the object in dispute increases scrutiny of the cow while masking the truthful target of Hindu nationalist violence, Muslim and Dalit people in India. Akhlaq's murder was described by reporters as being due to "rumors" of beef consumption, instead of locating his murder as a offense against him and his family for existence Muslim in India.

Is information technology beef or non?

Under Hindutva-driven cow protectionism, technologies like antibody tests, digital data collection, and social media platforms have come together to govern man and animate being populations. Several intervention methods have been proposed past the Indian government to monitor the beef ban and, in some cases, to curb vigilante activity emerging in response to information technology. These efforts include the speedy ELISA beef and water buffalo meat detection kit, placing cameras in slaughterhouses, assigning unique-identification numbers to cattle, and geotagging livestock farmers' houses.

With his team at Hyderabad-based Amar Immunodiagnostics Individual Express, the scientist Dr. Bhanushali developed a beef detection kit (BDK) and water buffalo detection kit. Bhanushali claimed the kit was his response "…as a scientist to the social problem arising from the misconceptions about beef," which he described as a 'menace.' The examination customized existing enzyme-linked immunosorbent analysis (ELISA) tests, which are commonly used in scientific laboratories as an antigen antibody test for things such every bit HIV, among others. The ELISA beef detection kit consists of 2 kits that simultaneously test small samples of meat to determine whether it is beefiness or not. The process takes 30 minutes overall and can be administered outside the lab.

Taken upwards past the Indian regime, Bhanushali'southward BDK boasts portability, speed, and relative cheapness for efficient dispersal. Officials from Maharashtra, a land in western India, have purchased over a hundred ELISA kits that were passed out to all xl-five of its mobile Forensic Scientific discipline Laboratory (FSL) vans, with the hope that quick BDK tests will cut downwards on meat samples being sent to FSL buildings, which usually receive 100-200 meat samples for testing each month. Kits will exist kept in FSL vans stationed in every Maharashtrian district for law to test meat from people suspected of selling or consuming moo-cow meat. As such, police will have the opportunity to accurately verify or debunk 'suspicions' of beefiness consumption and challenge or reinforce vigilante activity. Other state governments, including Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh, accept besides expressed an interest in purchasing kits.

The promise is that BDKs will lengthened tensions and decrease violence. Nonetheless, their expected effectiveness in curtailing vigilante violence is questionable. Our analysis of media articles reporting on authorities distribution of beefiness detection kits indicates that BDKs piece of work as a surveillance apparatus, where citizens cocky-discipline and law others—oft via the spread of rumors similar those that led to the murder of Mohammad Akhlaq. Given that over half of vigilante attacks are inspired by rumors it is unrealistic to hope that beef testing kits will stop a murderous mob. If hearsay is sufficient incitement for people to kill a fellow human, information technology is unlikely that they would be willing to suspension for half an hour to consider the merits of a scientific test issue before proceeding to comport out their mission or give up the hunt, equally the case may exist. Farther, if later thirty minutes the meat tests positive for beef, violence might ensue because of kit results. In questioning and testing whether a sample of meat is beefiness or not, beef detection kits legitimize the beefiness ban, motivated by Hindu nationalism. Beef detection kits locate the tension of the beef ban as an issue of scientific measurement, farther embedding and obscuring the political nature of the beefiness ban as an attack on Muslim and Dalit people in India.

Will technologies like beefiness detection kits actually reduce vigilante violence? And is safety really fifty-fifty the goal?

As such, governmental use and distribution of the scientific beef detection kit must be understood within the Indian context of the beef ban. Beef detection kits are explained as improving efficiency, curbing vigilante violence, and reducing sales, consumption, and smuggling of beef. This applied science is presented as scientifically objective. However, science is neither apolitical nor unbiased, evident even in Bhanushali'southward stated motive for creating a beef detection kit. Scientific knowledge and expertise grant objectivity through technologies such as beef detection kits, which allows the government to discipline and marginalize some populations. In response to the death of Mohammad Akhlaq and his son, the police stated, "We have been told that a group of people entered the temple and used a microphone to make the announcement [that Akhlaq's family was storing and consuming beef]. Nonetheless, investigations are still underway. We practice not know if any of the accused are associated with the temple. We have collected meat samples from Akhlaq's business firm and sent information technology to the forensics section for examination." By using this 'objective' scientific tool to investigate the source of the meat before the murder, the police effectively trivialized the crusade of violence washed to Akhlaq and his son and to many other Indians who accept experienced violence due to the beef ban.

Cow vulnerability

The emphasis on the scientific origins of beef detection kits obscure the political, social, and discriminatory basis of the ban on beef and its furnishings on brute populations it seeks to "protect." While the stated intent aims to counter cow vigilantism, the evolution of these new technologies instead normalizes the banning of beef in Republic of india, and extends the government'southward power to monitor certain groups, including the very cows whom it aims to protect. Past providing tools whose potential "success" relies upon an increased policing of Muslims and Dalits and the digital objectification of cows, political technologies can increment the vulnerability of parties across the human being-nonhuman spectrum.

By deeming the protection and management of cattle a public affair, the state is able to extensively police force and monitor cows, serving—by extension—as a way to surveil and police their owners, managers and users, who are often Muslim and Dalits. Despite seeming at odds, marginal human groups (Muslims and Dalits) share with non-human groups (cows, other bovines, non-bovines) a vulnerability to bodily violence through objectification, surveillance, and dispensability.

Surveillance technologies work to regulate and surveil cows. These technologies include the use of cattle unique-identification (UID) numbers, purportedly to increase dairy productivity through greater supervision of those who ain cows. The registration number of these cows is linked to their owners' Aadhar number, India'southward recently enacted social security scheme. Further, the country has widely discussed moo-cow UID benefits in curbing moo-cow smuggling and thereby increasing condom. The linkage betwixt cow surveillance and safety was made clear during an early tagging instance of Muslim-endemic cattle under the pretext of national security. Farmers are deemed responsible for tagging and oftentimes documenting cattle, wherein the prevalence of untagged cows can reflect on their owners' non-compliance, who can so be fined. Furthermore, the unique data collected for each moo-cow and recorded in a governmental database linked to the cow's UID prioritizes the cow's reproductive potential and economic contributions. Data collected includes identifiable markings, age, weight, and also lactation capacity, insemination record, and number of births.

Missing from the collected data are the brute'south atmospheric condition exterior of their reproductive and economic capability, or what means were taken to increase or heighten their (re)productive potential that might actually increase bodily violence. Deeming cows as existence mishandled, out of line, or calling their meat illegal then calls into scrutiny the public condition of Muslims and Dalits, and discredits their private actions of moo-cow sales and ownership. Individuals belonging to these groups share vulnerability with the moo-cow, and are similarly deemed out of line, unacceptable, and illegal.

Political technologies have increased vulnerability across the human-nonhuman spectrum.

The sacrality of the moo-cow causes it to lose its beast status. The cow instead works equally a symbol of the nation—an object to be controlled and regulated. By extension, cow meat no longer represents a bovine animal; cow meat becomes instead evidence of human law-breaking. When tested, non-moo-cow meat is discarded and labeled less worthy of protection. The seizure and testing of meat enacts violence on cows and not-moo-cow animals, reinforcing a bovine/not-bovine hierarchy. This shared vulnerability between marginal human and non-human being groups reveals ability structure and provides a starting betoken to challenge the condition quo.

Human and not-human shared vulnerabilities are increased through technologies such as beef detection kits, where cows are considered as belonging by virtue of sacredness and dairy productivity, and Muslims and Dalits are just contingently included through immense cocky-disciplining. The precarity in such belonging implies the disposability these groups experience, as witnessed in the violence washed to Akhlaq's family based on rumors, the inadequate police response to such violence, and of the solitude and disposal of all meat after it has been surveilled and tested. In recognizing the instability of such belonging, shared vulnerability could help to counter a cow protectionist approach that continues to objectify and surveil Indian subjects, instead assuasive for engagements that recognize more fully the sense of being of humans and non-humans.

Featured Prototype: Close-up of a cow in India. Photo by Audun Bie, @audun.bie, December, 2016.

A. Parikh is a Lecturer in the Section of Geography at Dartmouth College. She uses an intersectional gendered lens to await at questions of urban ecology belonging in globalizing South Asian cities facing the twin pressures of global capitalism and nationalist patriarchy. Website. Twitter. Contact.

Clara Miller has a B.S. in Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies from The Pennsylvania State Academy. Contact.

Source: https://edgeeffects.net/beef-testing-beef-ban/

0 Response to "How Is Beef Ban Against Nationalism"

Post a Comment